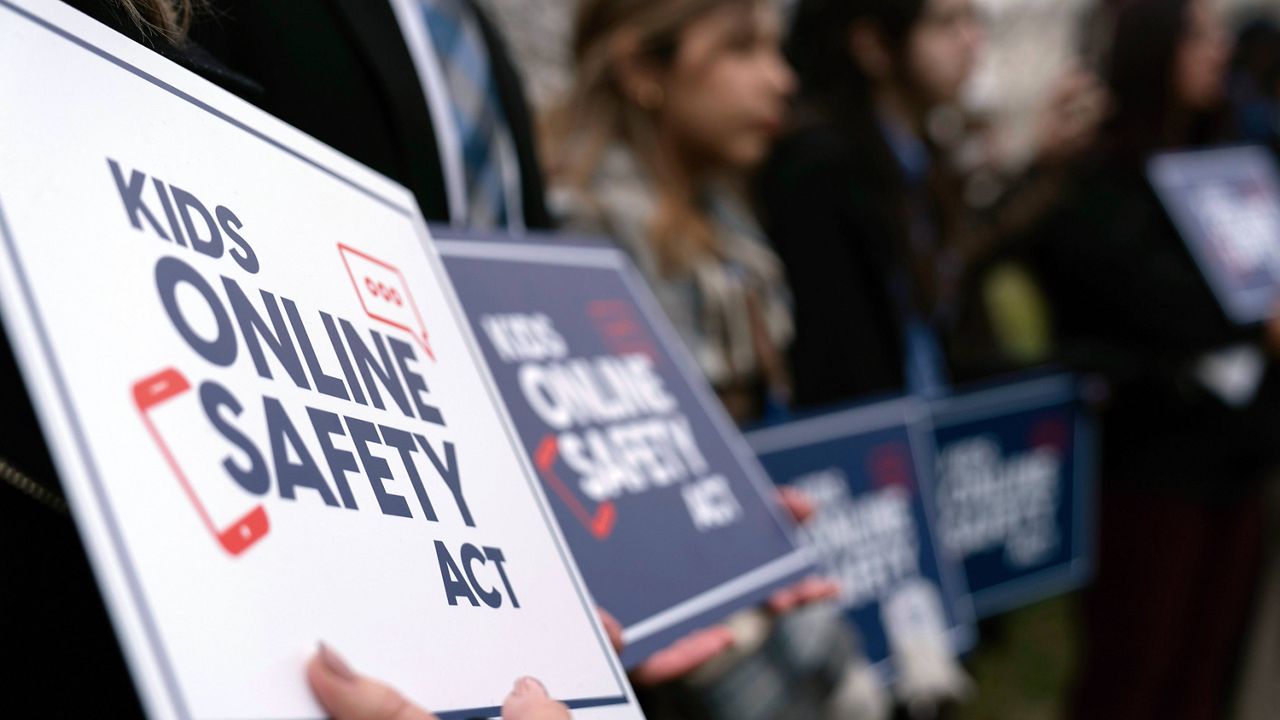

Last week, the Senate unveiled yet another iteration of the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), this time reportedly influenced by input from X CEO Linda Yaccarino. Despite these eleventh-hour adjustments, the bill remains fundamentally flawed and continues to threaten the online speech and privacy rights of all users. Far from addressing its foundational issues, this update cements KOSA as an unconstitutional censorship bill—one that neither adequately protects children nor shields platforms from liability.

Here's ads banner inside a post

Cosmetic Changes That Miss the Mark

The authors of the updated bill tout a key modification they claim reduces its potential impact on free speech. Specifically, the addition of a sentence to the “duty of care” provision purports to safeguard speech protected under the First Amendment. However, this new language is little more than window dressing.

The bill’s “duty of care” provision compels platforms to mitigate harms such as eating disorders, substance use disorders, and suicidal behaviors. While these harms are ostensibly tied to platform design, in reality, they often stem from user-generated content. The amendment states that “Nothing in this section shall be construed to allow a government entity to enforce subsection (a) [the duty of care] based upon the viewpoint of users expressed by or through any speech, expression, or information protected by the First Amendment.”

Here's ads banner inside a post

But this adjustment sidesteps the true problem: the duty of care applies to platforms, not individual users. It is platforms that are held accountable for disseminating content that regulators deem harmful to minors. This means that legal content could still subject platforms to liability if it is perceived to violate the duty of care—even if that content is protected by the First Amendment. The amendment provides no meaningful shield against this.

.webp)

Consider a forum on Reddit dedicated to supporting individuals recovering from eating disorders. While the discussions in such a forum may be entirely legal and even life-saving, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) could still penalize Reddit for allowing minors to access it. Similarly, LGBTQ+ support groups or algorithm-recommended posts discussing substance use could trigger liability. Platforms remain exposed to punitive action for enabling access to these spaces, rendering the amendment ineffective.

Here's ads banner inside a post

A Misstep by X’s Leadership

It is especially troubling that X’s leadership, which should understand these implications, played a role in crafting this language. By failing to distinguish between immunizing user expression and protecting platforms from liability, the bill’s authors—and X’s collaborators—have left a gaping hole in its supposed protections. Rather than addressing the fundamental risks to free speech and online community-building, this “fix” merely highlights a lack of understanding of how the law would operate in practice.

Compulsive Usage Clause: Another Vague Mandate

One of KOSA’s persistent flaws is its reliance on a poorly defined list of harms. The latest draft attempts to address this by requiring that harms like “depressive disorders and anxiety disorders” have “objectively verifiable and clinically diagnosable symptoms that are related to compulsive usage.” While this may appear to narrow the bill’s scope, it actually introduces new ambiguities.

The definition of “compulsive usage” remains frustratingly vague: “a persistent and repetitive use of a covered platform that significantly impacts one or more major life activities, including socializing, sleeping, eating, learning, reading, concentrating, communicating, or working.” Without clear criteria, platforms are left guessing what constitutes “persistent and repetitive use” and how it might “significantly impact” a user’s life.

For example, is a teenager who spends hours on Snapchat maintaining friendships exhibiting “compulsive usage”? What about an adult who loses sleep over an exciting YouTube video? Even benign or positive online interactions could be construed as “significant impacts” under this vague standard. This lack of clarity would likely lead platforms to overcorrect, removing or restricting a wide range of content to avoid potential liability.

An FTC Free to Weaponize the Bill

The updated language does little to curb the FTC’s potential to enforce KOSA broadly. An FTC chair under a politically charged administration could wield KOSA as a tool to suppress content deemed undesirable. This is particularly concerning given the stated views of Andrew Ferguson, the incoming FTC Chair nominee. Ferguson has made inflammatory comments about “fighting back against the trans agenda,” raising concerns about the types of content that might be targeted under his leadership.

Even the mere threat of enforcement could force platforms into compliance, leading to widespread censorship and the implementation of invasive age verification measures. These outcomes would occur regardless of whether the FTC ultimately takes action, as platforms would likely self-regulate to mitigate risk.

Censorship Hidden in Must-Pass Legislation

Adding to the controversy, lawmakers appear poised to bundle KOSA into a must-pass funding bill, bypassing the rigorous debate such a far-reaching law deserves. This tactic is as troubling as the bill itself. A law with such profound implications for free speech and online privacy should not be slipped through Congress without proper scrutiny.

KOSA’s fundamental flaws—its vague definitions, its potential to penalize platforms for hosting protected speech, and its chilling effect on online discourse—remain unresolved. No amount of last-minute tinkering can salvage a bill that forces platforms to police lawful content and trample on the rights of internet users. It is critical that representatives reject any attempt to shoehorn this dangerous legislation into a continuing resolution.

Why KOSA Fails to Deliver on Its Promise

The Kids Online Safety Act, even in its revised form, remains an overreaching censorship bill masquerading as a child safety measure. By failing to adequately address its constitutional shortcomings, the bill poses a threat to both children and adults’ ability to access and share information online. Rather than protecting young users, KOSA risks stripping them of essential resources and communities while setting a dangerous precedent for government overreach in the digital sphere.

Congress must resist the temptation to pass this flawed legislation under the guise of protecting children. Instead, lawmakers should focus on crafting thoughtful, narrowly tailored solutions that address genuine harms without sacrificing the free speech and privacy rights of millions. In its current form, KOSA is not the answer—and it never was.